A Symposium on the Four Procedures

Where things get a little weird.

Editorial note: Welcome! If this is your first visit, please read the introduction to the project here. And a quick note: at the urging of several Zen teachers, I’ve decided to use the more accurate and inclusive title ”Eyes of Humans, Eyes of Gods“ to translate 人天眼目, instead of “Eyes of Men and Gods.”

Anyone who’s studied Western philosophy is familiar with Plato’s legendary Symposium, a drinking party where various luminaries—Sophocles, Phaedrus, Agathon, Aristophanes—analyze the nature of love, debate the virtues of pedophilia, encounter attacks of hiccups, and speculate on whether human beings were originally meant to have four arms and four legs. This symposium, alas, isn’t that. Drinking-and-writing-poetry parties were a major part of the Chinese literary tradition, and Buddhist monks sometimes took part, but to throw a party, you have to start with a group of living guests. Zhizhao, on the other hand, creates a symposium of the ancestors: masters of the Linji school who mostly lived long before he was born, all assembled to comment on Linji’s Four Procedures, which I introduced in the last post.

Where did Zhizhao find all of these comments? My guess is he assembled them the way a scholar of his age would, by painstakingly sorting through individual commentaries on the Linji Lu and copying out the relevant passages in order to compare them. It’s likely that many (if not all) of the Linji school masters quoted below wrote their own full-length commentaries, all of which are now lost. The practice of assembling multiple commentaries on one source passage is very common in the Chinese tradition; you can get a sense of this by reading Red Pine’s excellent translation of the Diamond Sutra, which includes short passages of commentary from a variety of Chinese sources (and some Sanskrit ones as well). The use of “capping phrases” and other similar devices in Zen texts is probably just an extension of the same idea, though I’ll leave it to the scholars to figure that one out.

Reading these capsule biographies, it’s important to remember that while the Linji school in the 12th century was enormous and powerful, pretty much the zenith of Chinese Zen as a social institution, the “Linji school” barely existed at all until the sixth generation master Shishuang (listed below) popularized Linji’s teachings and the Linji Lu in the early decades of the Song dynasty, about 200 years before Zhizhao published Eyes of Humans, Eyes of Gods. Shishuang was Linji’s hype man, so to speak. Just as, much earlier in Zen’s Chinese history, Shenhui hyped up Huineng, the purported Sixth Patriarch, and in doing so created the “Sudden” versus “Gradual” (or Southern versus Northern) doctrinal schism more or less out of thin air.

As John McRae puts it in Seeing Through Zen, transmission lineages are “as strong as they are wrong.” Zhizhao obviously had a strong motivation to select commentaries that went straight back through the Yangqi branch of the school to Linji himself, affirming the notion of an unbroken succession of Linji’s dharma from the master’s words to his own time, three centuries later. (For a comparison to the English-speaking world, imagine a line of transmission stretching back from 2024 to Isaac Newton, who died in 1727.) But we don’t actually know very much about these early teachers in the generations after Linji, who likely lived lives of poverty and deprivation in the violent and tumultuous last years of the Tang dynasty. (We also don’t know very much about Linji himself; the Linji Lu was heavily edited and revised during the Song, to fit the definition of the school promoted by Shishuang and others.) So much of the history of what we know think of as “Zen” was being formed in those years in interactions between people not included in these canonical, school-supported texts—nuns, lay practitioners, renegade monks who never received official transmission, or just obscure masters who happened to disappear in remote temples without heirs or powerful friends to pay for stupas or other commemorations.

Canonical as these teachers may be, however, this is still the Linji school, where bizarre utterances and non sequiturs are the order of the day. Here are some of the lines I could barely make sense of:

達觀頴云。家裏已無回日信。路遙空有望鄉牌。 / Daguan said: “Inside the home, there is no return letter; in the middle of the country road, there is a signboard.”

明云。須信壺中別有天。/ Ciming said: “It must be that whatever is in this pot is also present with the gods.”

吾云。剛骨盡隨紅影沒。苕苗總逐白雲消。 / Daowu said, “Hard bones fade inside a red shadow. The reeds disappear under white clouds.”

I could really use some input from other Chinese translators/scholars in these cases. And surely other places as well.

The abstruse nature of some of these comments brings to mind Dahui Zonggao’s sharp critiques of the literary and poetic side of the Linji school; Dahui suppressed circulation of The Blue Cliff Record for this reason, even destroying the blocks it was printed on, and that essential koan anthology essentially fell out of circulation for several centuries as a result. We don’t know whether Zhizhao ever met or studied with Dahui, or what Dahui would have thought of Eyes of Humans, Eyes of Gods; I’ll write more about this subject in a later post.

Here are the symposium members, in chronological order. I’ve drawn some of this information from Andy Ferguson’s Zen’s Chinese Heritage and some from other online sources and databases in English and Chinese.

Nanyuan Huiyong 南院慧顒 (860–930) was a disciple of Xinghua Cunjiang 興化存奬, one of Linji’s dharma heirs. From Zen’s Chinese Heritage: “He came from ancient Hebei. Nanyuan was extremely strict and uncompromising in his approach to teaching Zen. He lived and taught at the “South Hall” (in Chinese, Nanyuan) of the Baoying Zen Monastery at Ruzhou. Nanyuan is the most important teacher of the third generation of the Linji school, and is a direct link in the lineage that stretches down to modern times.”

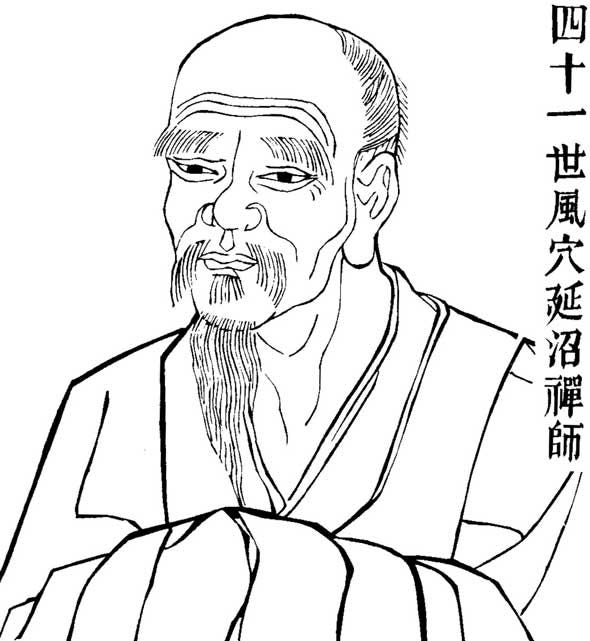

Fengxue Yanzhao 風穴延沼 (896–973) was a disciple of Nanyuan Huiyong. He appears in cases 38 and 61 of the Blue Cliff Record. From Zen’s Chinese Heritage: “Fengxue came from ancient Yuzhou. He studied Confucianism as a youth and failed on his first attempt to pass the state civil exams. In disappointment, he left home and entered the Kaiyuan Monastery, where he received ordination under the Vinaya master Zhigong. He delved into the Lotus Sutra and practiced the zhiguan style of self-cultivation used in the Tiantai school. Fengxue traveled to broaden his understanding and studies. At the age of twenty-five, he studied with Zen master Jingqing Daofu. Still unsuccessful at uncovering the root of Zen, he continued his travels, and eventually studied under the rigorous Zen master Nanyuan Huiyong. He remained with Nanyuan for six years, finally awakening to the Way and becoming his teacher’s Dharma heir. In 931, Fengxue traveled to Ruzhou, where he began teaching at the already old and dilapidated Fengxue Temple. There he derived his mountain name. News of Fengxue’s ability spread, and before long Zen students gathered around him. The temple’s poor physical condition was beyond repair, however, and in the year 951 Fengxue and his students moved to the newly built Guanghui Temple. Fengxue remained there as abbot for twenty-two years.”

Shoushan Xingnian 首山省念 (926–93) A fourth generation Linji school master who most likely is responsible for preserving the Linji Lu and other school materials during the widespread warfare and social disruption that accompanied the fall of the Tang Dynasty. According to the Linji school transmission records, he was the teacher of Fenyang Shanzhao 汾陽善昭, whose commentary shows up in many other parts of the Linji section of Eyes of Humans, Eyes of Gods. From ZCH: “A disciple of Fengxue Yanzhao. He came from ancient Laizhou (now in Ye County in Shandong Province). Shoushan is remembered for having concealed and carried on the Linji lineage during the turbulent end of the Tang dynasty. As a young man, he left home to live at Nanchan Temple, where he took the monk’s vows. Later, as he roamed China, Shoushan daily chanted the Lotus Sutra and thus gained the nickname “Nianfahua [‘Chanting Lotus Sutra’].””

Ciming 慈明 is an alternate name/title for Shishuang Chuyuan 石霜楚圓 (986–1039), the sixth generation Linji school Zen master who brought Linji’s teachings to Hunan, in south/central China, and promoted them widely, creating the “Linji school” as it would have been known in Zhizhao’s time. He was the dharma heir of Fenyang Shanzhao 汾陽善昭. His own dharma heirs, Yangqi Fanghui 楊岐方會 (992-1049) and Huanglong Huinan 黃龍慧南 (1002-1069) each founded their own separate transmission lines, which eventually arrived in Japan as competing Rinzai schools. Zhizhao was part of the Yangqi line, which eventually became the only extant line of the Linji school in China (and eventually absorbed all of Chinese Zen).

Shimen Cizhao 石門慈照 (965-1032) was a contemporary of Shishuang, presumably also of the sixth generation of the Linji school. There’s relatively little biographical data available, but here’s a taste: “After becoming a monk, he went to pay homage to Baizhang Daochang, then went to pay homage to Shoushan Mountain and reflected on it, which led to great enlightenment. In the third year of Jingde (1006), he lived in Shimenshan, Xiangzhou. In the fourth year of Tianxi (1020), he moved to Taiping Xingguo Zen Temple in Guyinshan.”

Daguan Tanying 達觀曇穎 (989-1061) was an heir of Shimen Cizhao, presumably in the seventh generation of the Linji school. From a work by Zen Master Xingyun: “He was a native of Qiantang, Hangzhou, Zhejiang. He became a monk in Longxing Temple at the age of thirteen. In his youth, he traveled to the capital to study and read widely. He first studied under Zen Master Dayang Jingxuan, and later studied under Zen Master Guyin Yuncong (aka Shimen Cizhao) and obtained his teachings. Later, he moved to Longyou Temple in Jinshan, Runzhou (now Zhenjiang, Jiangsu Province).”

Fahua 法華 is another name for Baiyun Shoudian 白雲守端 (1025-1072), a somewhat obscure Linji school monk probably of the eighth generation, who left behind a two-volume Collected Sayings text even though he died relatively young. He was an heir of Yangqi Fanghui.

Yuanwu Keqin 圓悟克勤 (1063–1135) is the ninth-generation Linji school master who compiled the Blue Cliff Record and was the teacher of Dahui Zonggao. Yuanwu and Dahui together reshaped the Linji tradition (and all of subsequent Zen) in the 12th century.

Daowu 道吾 is unknown. There were, inconveniently, no fewer than four Linji monks named Daowu during the Song dynasty, none of whom were very well known, and any of whom (in theory) could be the source of these quotations: Daowu Wuzhen 道吾悟真, Daowu Zhongyuan 道吾仲圓, Daowu Chufang 道吾楚方, and Daowu Rufeng 道吾汝能.

Nanyuan posed a question to Fengxue. “Tell me about the Four Procedures,” he said. “What is their underlying meaning (dharma)?”

Xue replied: “Common speech does not obstruct common thinking. It degenerates into the wisdom of the sages. This is the student’s great sickness. [But] it is also a time for the use of skillful means. Use the wedge to take out the wedge.”

•

Nan then asked, “What do you think of ‘Take away the person, but don’t take away the situation’?”

Xue replied: “The student [subordinate] takes a golden ball out of the red-hot furnace and uses it to penetrate the teacher’s iron forehead.”

Shoushan said: “A person looks out and sees a thousand peaks in the distance.”

Fahua said: “White crysanthemums open their blossoms on a warm day. In a hundred years, the prince never encountered springtime.”

Ciming summed it up: “Shenhui polished Puji’s stone tablet.”

Daowu spoke truthfully: “In my hut, I sit at my leisure; the white clouds float above the very tips of the mountain peaks.”

Yuanwu said: “The old monk has eyes, but has never seen anything.”

Daguan said: “Inside the home, there is no return letter; in the middle of the country road, there is a signboard.”

Shimen wisely said: “The mountains, the rivers, and the whole great Earth.”

•

[Nanyuan said] “What about ‘take away the situation, don’t take away the person’?”

Fengxue said: “Quickly the grasses part, as if someone’s brains are cut in pieces. Disordered clouds break apart, their shadows flying everywhere.”

Shan said: “You hit someone once but they still don’t avoid you. The enemy is hard to get rid of.”

Fahua said: “In Heaven and Earth, there is no remedy. Quickly, accept the truth.”

[Unclear: Ciming said: “It must be that whatever is in this pot is also present with the gods.”]

Daowu said: “The red banners wave in all directions; sages and children give directions on the road.”

Yuanwu said: “The acarya asks about achieving natural intimacy.”

Daguan said: The vast ocean dries up; the teachings wither away in the end; the green mountains are ground up into dust.”

Shimen said: “The barbarian is lost behind the curtain.”

•

[Nanyuan said] “What about ‘take away both the situation and the person’?”

Fengxue said, “Even if you have to step on people’s feet, hurry! Use a whip on the horse, you don’t want to be late!”

Shoushan said, “Ten thousand people together made a burial mound. They worked until they were exhausted. What a pity!”

Fahua said, “The homeless man’s face turns red. Ordinary people and sages forget everything.”

Ciming said, “Inside China, the Emperor gives a warning. Outside the realm, on the frontier, the head of the army sets the law.”

[Unclear: Daowu said, “Hard bones fade inside a red shadow. The reeds disappear under white clouds.”]

Yuanwu said, “I accept it.”

Daguan said, “Heaven and earth are still empty. Whether under the sun or the moon, by the mountains or the rivers, where are the rulers and ministers of China?”

Shimen said, “Where are the Buddhas and patriarchs?”

•

“What about ‘take away neither the person nor the situation’?”

Fengxue said, “The Emperor remembers late spring in Jiangnan [the third month]. The partridges send up their cries; you can smell the fragrance of a hundred flowers.”

Shoushan said, “When you ask a question, you see clearly; when you answer, you answer intimately.”

Fahua said, “A cool breeze accompanies the bright moon. Nature is laughing with us.”

Ciming said, “We walk back and forth under the bright moon, enjoying the cool breeze.”

Daowu said, “Rain finally falling after a long drought, like encountering a friend in a foreign place.”

Yuanwu said, “I release it.” [“Released”]

Daguan said, “Orioles sing in the trees, and the earth is full of flowers. Under the sky, the guest wanders through spring grasses.”

Shimen said, “Question and answer can both be seen clearly.”

南院顒問風穴昭(亦作沼)云。汝道。四料揀。料揀何法。穴云。凡語不滯凡情。既墮聖解。學者大病。先聖哀之。為施方便。如楔出楔。

院問. 如何是奪人不奪境(首山等答皆附)穴云。新出紅爐金彈子。簉破闍黎鐵面門。首山云。人前把出遠送千峯。法華舉云。白菊乍開重日暖。百年公子不逢春。慈明圓云。神會曾磨普寂碑。道吾真云。庵中閑打坐。白雲起峯頂。圓悟勤云。老僧有眼不曾見。達觀頴云。家裏已無回日信。路遙空有望鄉牌。石門聰云。山河大地。

如何是奪境不奪人。穴云。芻草乍分頭腦裂。亂雲初綻影猶存。山云。打了不曾嗔。冤家難解免。華云。大地絕消息。翛然獨任真。明云。須信壺中別有天。吾云。閃爍紅旗散。仙童指路親。圓悟云。闍黎問得自然親。觀云。滄海盡教枯到底。青山直得碾為塵。門云。番人失[疊*毛]帳。

如何是人境俱奪。穴云。躡足進前須急急。促鞭當鞅莫遲遲。山云。萬人作一塚。時人盡帶悲。華云。草荒人變色。凡聖兩俱忘。明云。寰中天子勅。塞外將軍令。吾云。剛骨盡隨紅影沒。苕苗總逐白雲消。悟云收。觀云。天地尚空。秦日月。山河不見漢君臣。門云。有何佛祖。

如何是人境俱不奪。穴云。帝憶。江南三月裏。鷓鴣啼處百花香。山云。問處分明答處親。華云。清風伴明月。野老笑相親。明云。明月清風任往來。吾云。久旱逢初雨。他鄉遇故知。悟云放。觀云。鶯囀上林花滿地。客遊三月草侵天。門云。問答甚分明。

Image credit: this is a traditional Chinese woodcut of Fengxue Yanzhao, reading, “Of the 41st generation [of Zen transmission starting with Sakyamuni Buddha], Fengxue Yanzhao, Zen master.”

https://idp.bl.uk/blog/scribes-at-dunhuang-pens-paper-and-punishments/